Scientific Name: Fratercula arctica

Size:

Approximately 28-30cm

Description:

The Atlantic Puffin is a popular bird with the British public because of its bright appearance and charisma. Its most recognisable feature is its colourful yellow, blue and red striped bill. This influx of colour is there for the breeding season, in which case, if you saw a puffin in the winter, the colours would be somewhat duller and the bill smaller. This is because the bill-plates are shed when not required.

Our winter puffin also has a duller face that appears more grey in colour. The juvenile is fairly similar to a winter adult but the bill is even smaller and darker. The young puffin’s black and white elements are adjoined by a dull grey, making the separate hues less distinct.

In the UK, you’re most likely to see the puffin in a breeding colony during the spring or summer. Its appearance is striking as it has a neat black back, collar and ‘hat’. The eye looks almost sad because of its upward triangular appearance and a ‘clown-like’ impression is completed by the bright bill and orangey-red legs. The puffin’s face and underparts are white, which make the colours really stand out.

The puffin’s voice is alike to a deep ‘groan’ that is reacting with interest to a conversation and then mild amusement with a slight laugh.

Identifying Sex:

At a glance it is not particularly easy to tell apart male and female puffins. The males tend to be slightly larger with a bigger bill length and depth. There are overlaps between the sizes of both sexes though, which can make identification confusing.

During the breeding season, just before and after laying eggs, the females generally have an enlarged cloaca. It will sometimes have purple vascular streaking due to swelling. At other times identification isn’t always clear cut as individuals may have larger or smaller cloacas than expected for their sex.

Diet:

Puffins are good at diving and swimming, which is important as fish and sand eels form a large part of their diet. They have specially-designed bills that allow them to catch and hold multiple prey at one time. This allows the puffins to concentrate on the catch; pushing themselves forward with their wings, often around 20-30 metres below the surface.

The puffins often fish up to 5km from the colony but can stray farther for their prey, which include sand eels, capelin, saithe, rocklings, young cod, whiting, herring, young haddock and occasionally small crustaceans.

Breeding:

Puffin’s bills and feet are not only attractive but also serve the purpose of digging burrows to breed in. They’re not against breeding in unoccupied rabbit warrens or in crevices if needs be. They ideally want a burrow that is about 90cm deep with a small enough entrance to keep out most predators such as skuas.

Once they have found a good burrow, they like to use the same one each year, preferably with the same mate if they have bred successfully previously. They return to the breeding colony around March or April and take part in a courtship ‘dance’ with their chosen mate by bumping bills, waggling their heads and calling to each other. The puffins repair or dig their burrow together in preparation for the female to lay one egg, which they will take turns to incubate.

After 36 – 43 days the egg hatches producing a very fluffy, dull-coloured chick. The parents attentively feed the chick until it is around 38 – 44 days old when it is finally ready to leave the burrow and fledge. It takes its first uncertain flight to the sea in darkness to avoid predators and then it begins to swim into its new independent life.

The young puffin will most likely remain at sea for its first winter. It will be unlikely to breed until it is 5 or 6 years old. At this point it will seek its own burrow most likely on a grassy clifftop. If lucky, the puffin could live into its 20s or 30s albeit facing challenges along the way.

On a Personal Note:

Anyone who has seen our smallest breeding auk in the flesh would likely agree that the experience is very special. Puffins are extremely entertaining to watch. They flap frantically, calmly manoeuvre to land and then waddle through the hustle and bustle back to their burrows.

We’ve enjoyed watching puffins on Skomer Island (Wales), Inner Farne (England) and St Kilda (Scotland). In each location the experience varies greatly. The close views on Skomer and Inner Farne allow an intimate view of the puffin’s lives. However, the dramatic backdrop of St Kilda makes the puffins seem far less comical and instead impressively capable.

The constant harassment from skuas and gulls do not deter the puffins from feeding their chicks. Instead they may give up part or all of their catch; finding themselves back at square one.

The noise and activity of any seabird colony has a great appeal to us at Embrace Nature UK. Therefore, if you have never seen puffins in the UK, we strongly recommend the experience. See our ‘useful links’ below for more information.

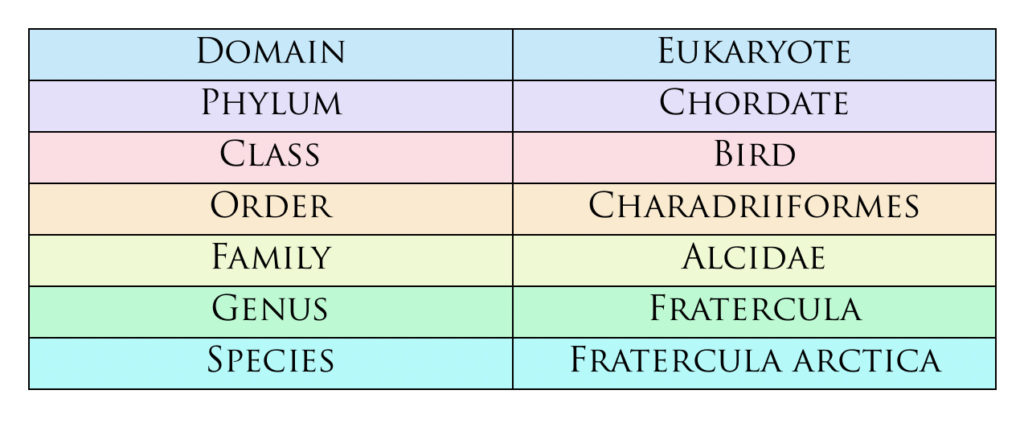

Puffin Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

If you would like to visit Skomer island, follow this link to learn more.

If you intend upon visiting Inner Farne this year, this National Trust link may help you plan your trip.

You may prefer to see puffins on Hirta, St Kilda, in which case you might find these links useful for National Trust for Scotland and Kildacruises.

Additional Reading:

Comments

We love to know your thoughts on our articles so greatly appreciate you taking the time to comment. We may be unable to reply directly but are in the process of creating a FAQs page to answer any questions. All comments are currently checked before they’re posted so they do not appear immediately on the website.

Thank you for visiting www.embracenatureuk.com!