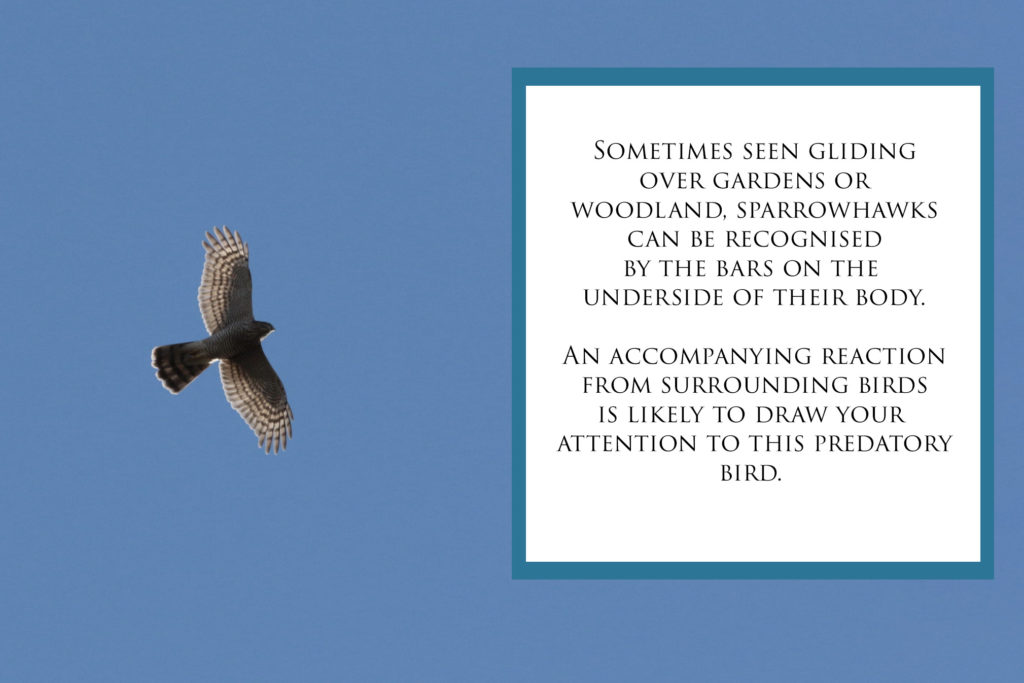

Sparrowhawk Scientific Name: Accipiter nisus

Size

A sparrowhawk has a wingspan of approximately 60 to 75 cm.

Description

The sparrowhawk is arguably the bird of prey you’re most likely to see in your garden. However, unless you make a point of looking for it, there’s a fair chance you’ll miss it altogether. Nevertheless, bundles of feathers found in the garden or woodlands often indicate the presence of one of these birds.

The sparrowhawk is an ambush hunter and whilst it may often appear suddenly, once seen, its appearance causes uproar amongst other bird species.

The best views of sparrowhawks are usually afforded when they stop to feed on their prey. This may only be a fleeting view if the prey is small, however, for a larger meal they can remain in good view for some time.

Identifying Sex

When you can see the sparrowhawk properly, you will probably notice how distinctive it is. Females are larger than males and are close to monotone with a brownish-grey back and dark bars over her pale underside. In contrast, the male is not only smaller but brighter in colour. His back is a bluish-grey colour and the barred underparts have a reddish-brown hue. Both males and females have a long tail but their rounded wings are unexpectedly small compared to their body size.

Juveniles are not terribly dissimilar from adults with brown bars on their underparts and a brown back. However, identifying a young bird’s sex is somewhat more difficult than that of an adult.

Diet

Despite the name, sparrows are not the only bird on the menu. Female sparrowhawks are large enough to take prey up to the size of pigeons, whilst the smaller males can catch prey the size of a blackbird.

Breeding

Sparrowhawks may usually be difficult to see, but in the breeding season they become even more elusive as they take to the trees to prepare a nest. They build their nests out of twigs, down and flakes of bark. The nest is substantial and takes several weeks to construct. Once their work is done, the female produces the eggs in time to utilise the increased food source coming from other breeding birds. She will lay 3 – 6 eggs but at intervals, normally by a couple of days each during May. By doing this, she reduces the risk of losing her chicks due to lack of food.

After a 32-35 day incubation period, the female helps the chicks to break out from their eggs. The male becomes responsible for feeding the chicks and female as she remains on the nest to incubate the young. When the chicks reach a point where they can be left alone, the female may help with the hunting if they are short of food.

Around 4 weeks after hatching, the chicks are ready to fledge but don’t go far. The smaller males fledge first with the larger females following after. The chicks keep returning to the nest whilst they prepare for adulthood. The sparrowhawks celebrate the arrival of their fully developed feathers by starting to hunt.

On a Personal Note

I find sparrowhawks to be an exciting bird of prey but rarely see them. With a keen eye and observant ears I have seen more sparrowhawks in recent years than previously. I have found a good sign to either be a roar of bird alarm calls, or a scattering of birds followed by eerie silence. The bird may be hard to see but could just be a silhouette high above the garden or woodland.

The photographs on this page were all taken in the Embrace Nature UK garden – most of which were on one day when the trusty bird alarms sounded indicating a successful hunt. Whilst the collared dove did not fare well, we had the benefit of observing the sparrowhawk for a prolonged time.

Some people see sparrowhawks as ‘the enemy’ as they hunt popular garden birds. However, there is no proof that the sparrowhawk’s hunting activities harms bird populations. The sparrowhawk is simply doing what is necessary to survive. They are a beautiful and charismatic bird that leaves a lasting impression. Those lucky enough to see the sparrowhawk, are unlikely to forget the experience in a hurry.

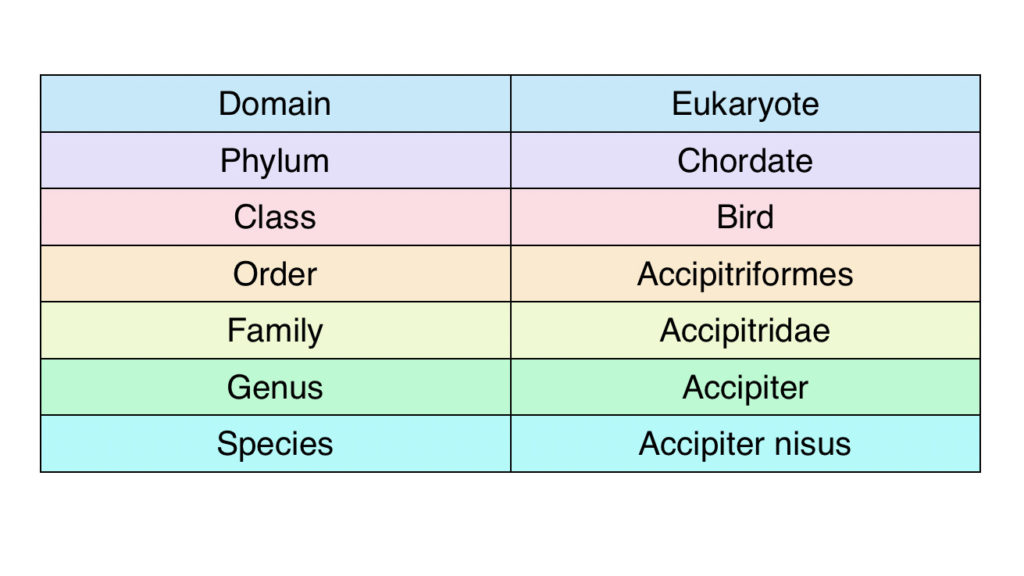

Sparrowhawk Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

Read this interesting article about sparrowhawks on the Autumnwatch website; “Friend or Foe?”.

Comments:

We love to know your thoughts on our articles so greatly appreciate you taking the time to comment. We may be unable to reply directly but are in the process of creating a FAQs page to answer any questions. All comments are currently checked before they’re posted so they do not appear immediately on the website.

Thank you for visiting www.embracenatureuk.com!

Northern Gannet, Scientific Name: Morus bassanus

Size:

The northern gannet has a wingspan of approximately 165 – 180cm.

Description:

The first thing to notice about the northern gannet is its size. It’s the largest of our seabirds in the UK and is hard to miss! The adult appears primarily white, however the strong black wingtips are often obvious, even at a distance. Closer to the bird, you will see the subtle yellow colour of its head and the blue ring around its eye as well. It also has black markings lining its face and bill. The gannet’s bill is very long, strong and sharp, adding to the bird’s distinctive look.

The overall colour of younger birds is dependent on their age and they can range from very dark to white with speckled brown patches. However, they still have the noticeably gannet-like overall appearance with their hefty wings and long bill.

Identifying Sex:

At first glance it is not necessarily possible to identify a male northern gannet from a female, although size or colouration may occasionally lead to accurate placing.

Using behaviour to identify sex can be more reliable although is not watertight. For example, males primarily collect nesting material, however females also occasionally perform this action.

Whilst you cannot be 100% sure of the sex from a distance, becoming familiar with the birds may allow you to make an educated guess that a bird is more likely to be a male than a female and vice versa.

Diet:

The northern gannet is known for its spectacular diving ability. It achieves a deeper dive by starting high over the water and pulling its wings into its body moments before impact. Whilst the dive itself is impressive, the bird struggles to become airborne again.

The risks attached to diving in this way are reduced by the gannet’s evolutionary adaptations such as membranes over its eyes, internal nostrils and pockets of air protecting its neck and head from the impact of the water.

This striking way of hunting looks exciting, but is, at the end of the day, a means to an end. If the gannet is lucky, the result is a fish about the size of herring or mackerel.

The Breeding Season:

Come January, male gannets are starting to return to their breeding colonies in order to make preparations for the oncoming season. They often return to the same nest each year and mate with the same female. gannets don’t begin to breed until they’re 4 years old and so in the meantime they observe the adult birds at work.

The younger birds may try making their own nest or even take over a deserted nest if there’s no bird around to defend it. The nest has to be constantly repaired though, which is done with a variety of materials. Seaweed is an obvious choice, although gannets will use whatever they can find. Sadly this includes plastics that can and do have a catastrophic effect on chicks.

Despite living within such close proximity to each other, these birds are very territorial. They will often fend off gannets of the same sex with a violent poke from their sharp bill. On the flip side, gannets are also renowned for their seemingly romantic mating dance. It’s important for coupled birds to maintain a close bond as the breeding season begins. Therefore they perform a display of tilting heads and tapping bills that enthrals spectators.

New Life:

The female gannet lays a single egg around late April to mid June. Both parents incubate the egg over the course of 44 days, until it hatches. The chick that emerges is then fed on regurgitated fish. Approximately ninety days later, the parents withdraw from feeding their youngster in order to prompt it to make its own way in the world.

The chick doesn’t leave the nest immediately, but instead takes around ten days to lose some weight and build strength in its wings ready for take-off. Its excess fat helps the chick in its early weeks of independence before it begins feeding itself.

If gannets are both lucky and successful in their survival, they can live into their thirties.

On a Personal Note:

We have had the good fortune to see a range of northern gannets in different locations across the UK including Pembrokeshire, Bempton Cliffs, Bass Rock and St Kilda. Each of these locations has offered a unique experience.

We had our closest encounter on Bass Rock, which allowed us the opportunity to see gannets at the nest. It is not difficult to identify gannets once you’ve seen them and so you can soon relax and enjoy watching their behaviour.

Northern gannets are not against stealing or acting violently. They’re incredibly entertaining at the nest as both of these actions happen regularly. They often steal nesting material from other gannets. Meanwhile the victim may be baffled by their magically reducing nest or perhaps they’ll catch the thief red-handed. The latter often results in aggressive squawking and attempted poking with its dauntingly sharp bill.

On the flip side, romance at the nest is not uncommon either. One of the highlights of watching gannets is seeing their elegant mating ‘dance’.

All in all, a gannet colony is a lively place to be with exciting behaviour happening left, right and centre. If you have not yet had the good fortune of watching gannets, head out to the coast during the breeding season. Check out our useful links below for good locations.

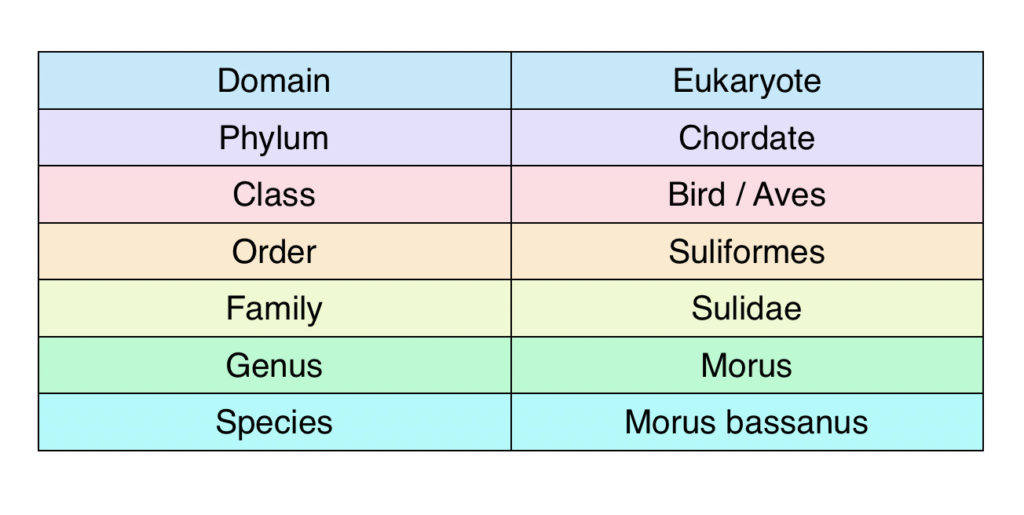

Northern Gannet Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

To head out and see gannets at the RSPB site at Bempton Cliffs, click this link to plan your visit.

To find out more about seeing gannets on the St Kilda archipelago, Scotland, click this link.

Comments:

We love to know your thoughts on our articles so greatly appreciate you taking the time to comment. We may be unable to reply directly but are in the process of creating a FAQs page to answer any questions. All comments are currently checked before they’re posted so they do not appear immediately on the website.

Thank you for visiting www.embracenatureuk.com!

Scientific Name: Fratercula arctica

Size:

Approximately 28-30cm

Description:

The Atlantic Puffin is a popular bird with the British public because of its bright appearance and charisma. Its most recognisable feature is its colourful yellow, blue and red striped bill. This influx of colour is there for the breeding season, in which case, if you saw a puffin in the winter, the colours would be somewhat duller and the bill smaller. This is because the bill-plates are shed when not required.

Our winter puffin also has a duller face that appears more grey in colour. The juvenile is fairly similar to a winter adult but the bill is even smaller and darker. The young puffin’s black and white elements are adjoined by a dull grey, making the separate hues less distinct.

In the UK, you’re most likely to see the puffin in a breeding colony during the spring or summer. Its appearance is striking as it has a neat black back, collar and ‘hat’. The eye looks almost sad because of its upward triangular appearance and a ‘clown-like’ impression is completed by the bright bill and orangey-red legs. The puffin’s face and underparts are white, which make the colours really stand out.

The puffin’s voice is alike to a deep ‘groan’ that is reacting with interest to a conversation and then mild amusement with a slight laugh.

Identifying Sex:

At a glance it is not particularly easy to tell apart male and female puffins. The males tend to be slightly larger with a bigger bill length and depth. There are overlaps between the sizes of both sexes though, which can make identification confusing.

During the breeding season, just before and after laying eggs, the females generally have an enlarged cloaca. It will sometimes have purple vascular streaking due to swelling. At other times identification isn’t always clear cut as individuals may have larger or smaller cloacas than expected for their sex.

Diet:

Puffins are good at diving and swimming, which is important as fish and sand eels form a large part of their diet. They have specially-designed bills that allow them to catch and hold multiple prey at one time. This allows the puffins to concentrate on the catch; pushing themselves forward with their wings, often around 20-30 metres below the surface.

The puffins often fish up to 5km from the colony but can stray farther for their prey, which include sand eels, capelin, saithe, rocklings, young cod, whiting, herring, young haddock and occasionally small crustaceans.

Breeding:

Puffin’s bills and feet are not only attractive but also serve the purpose of digging burrows to breed in. They’re not against breeding in unoccupied rabbit warrens or in crevices if needs be. They ideally want a burrow that is about 90cm deep with a small enough entrance to keep out most predators such as skuas.

Once they have found a good burrow, they like to use the same one each year, preferably with the same mate if they have bred successfully previously. They return to the breeding colony around March or April and take part in a courtship ‘dance’ with their chosen mate by bumping bills, waggling their heads and calling to each other. The puffins repair or dig their burrow together in preparation for the female to lay one egg, which they will take turns to incubate.

After 36 – 43 days the egg hatches producing a very fluffy, dull-coloured chick. The parents attentively feed the chick until it is around 38 – 44 days old when it is finally ready to leave the burrow and fledge. It takes its first uncertain flight to the sea in darkness to avoid predators and then it begins to swim into its new independent life.

The young puffin will most likely remain at sea for its first winter. It will be unlikely to breed until it is 5 or 6 years old. At this point it will seek its own burrow most likely on a grassy clifftop. If lucky, the puffin could live into its 20s or 30s albeit facing challenges along the way.

On a Personal Note:

Anyone who has seen our smallest breeding auk in the flesh would likely agree that the experience is very special. Puffins are extremely entertaining to watch. They flap frantically, calmly manoeuvre to land and then waddle through the hustle and bustle back to their burrows.

We’ve enjoyed watching puffins on Skomer Island (Wales), Inner Farne (England) and St Kilda (Scotland). In each location the experience varies greatly. The close views on Skomer and Inner Farne allow an intimate view of the puffin’s lives. However, the dramatic backdrop of St Kilda makes the puffins seem far less comical and instead impressively capable.

The constant harassment from skuas and gulls do not deter the puffins from feeding their chicks. Instead they may give up part or all of their catch; finding themselves back at square one.

The noise and activity of any seabird colony has a great appeal to us at Embrace Nature UK. Therefore, if you have never seen puffins in the UK, we strongly recommend the experience. See our ‘useful links’ below for more information.

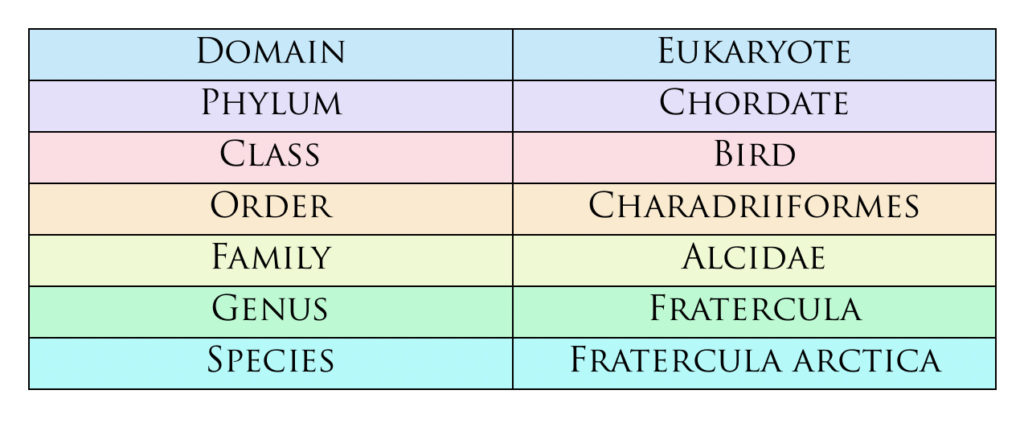

Puffin Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

If you would like to visit Skomer island, follow this link to learn more.

If you intend upon visiting Inner Farne this year, this National Trust link may help you plan your trip.

You may prefer to see puffins on Hirta, St Kilda, in which case you might find these links useful for National Trust for Scotland and Kildacruises.

Additional Reading:

Comments

We love to know your thoughts on our articles so greatly appreciate you taking the time to comment. We may be unable to reply directly but are in the process of creating a FAQs page to answer any questions. All comments are currently checked before they’re posted so they do not appear immediately on the website.

Thank you for visiting www.embracenatureuk.com!

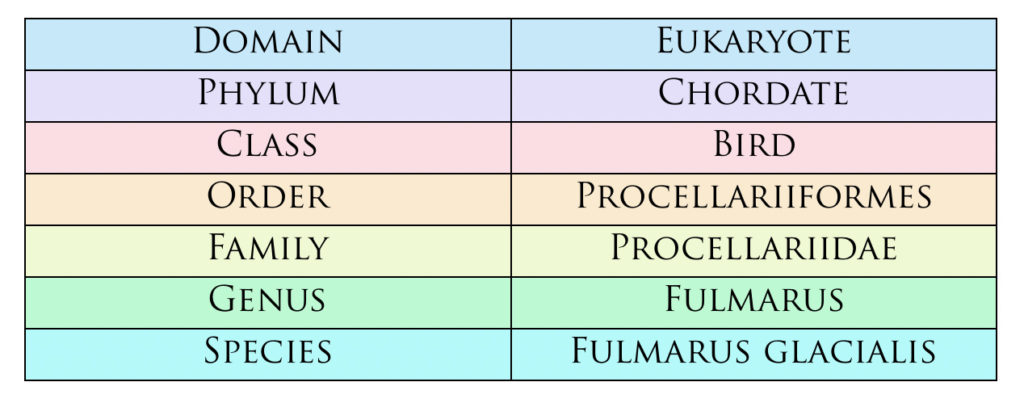

Scientific Name: Fulmarus glacialis

Size:

Length approximately 45cm, wingspan around 100 – 112cm

Description:

Fulmars are distinctive-looking birds with a bulky body, which is primarily white but for its grey back and wings. The wingtips are slightly darker than the rest of the wing. The bill makes the bird instantly recognisable as looks heavy with an obvious ‘tube’ on top. The fulmar is part of a group of birds often referred to as ‘tubenoses’ that have this feature. Many bird’s nostrils are contained within their bill but the ‘tubenoses’ are thought to use their unique feature to extract excess salt from their bodies that has been obtained when catching prey out at sea. It has been suggested that this adaptation also allows for a better sense of smell, which enables the birds to more easily find carrion. The bill is formed from a series of plates and has a hooked tip, that helps the bird keep hold of live prey.

The fulmar is the largest of tubenoses that breed in the UK. It has ‘stiff’ wings that are sometimes likened to blades cutting through the air. They seem to have no difficulty in flying and instead often glide with minimal effort. When juveniles lose their fluffy down they take on a very similar appearance to adults.

Whilst all of these features make the fulmar easy to recognise, a colour-morph exists that might confuse an observer. This alternatively plumaged bird is referred to as a ‘blue’ fulmar. The overall plumage is grey though the general appearance of the fulmar is still unmistakable. It is rare to see the ‘blue’ fulmar in the UK, however, you are more likely to see them in the North as the birds may visit from the Arctic.

Identifying Sex:

For the average bird-watcher, determining whether a fulmar is male or female is likely to be quite difficult. Their plumage is so similar that various studies ensued to try and find other ways of differentiating between sexes. A 2005 paper shows the research by Mark L. Mallory and Mark R. Forbes on fulmars in the Canadian Arctic. From measurements including head length, mass, bill depth and the size of the middle toe, they found that males usually are larger than females although some overlaps occur. Measurements of tail length proved not to provide a reliable comparison.

Diet:

Fulmars are pelagic (spend all but the breeding season at sea) and so their diet is mostly made up by fish, sand eels, zooplankton and carcasses from various creatures including whales and seals. They are thought to have a very good sense of smell, which leads them more easily to their food. This may also guide them to fishing boats, where they can enjoy a free meal. The waste from fishing boats is thought to have helped fulmar populations increase. The fulmars sometimes plunge dive for a shallow meal but they also pick food from the surface of the water; swallowing it straight away.

Breeding:

The UK enjoys large numbers of fulmars colonising the cliffs from around May until August each year during their breeding season. Once upon a time this wouldn’t have been seen in Britain as until 1878, the only part of the UK fulmars bred on was the St Kilda archipelago (Scotland). A community of people, who were reliant on birds such as the fulmar for survival, lived on St Kilda until August 1930. The changes in their lifestyle and population numbers has been thought to have affected fulmar populations and triggered their distribution to Shetland and beyond.

Fulmars return to the same partner and nest site each year with a few exceptions. They display to each other with bows, cackling and various other head and neck movements. Their partnerships are often long-lived with birds lasting into their 30s and in some cases to around 40 years old or more. A single egg is laid onto the cliff without the effort of a creating a purpose-built nest. For the first day the female incubates but passes the responsibility to the male for the next week whilst she’s away from the ‘nest’. They share incubation duties for the rest of the time in 3 or 4 day shifts. After 52 days the egg hatches prompting the parents to take turns finding food. For the first two weeks or so the chick has the company of one of its parents though after this time is often left alone whilst the adults forage for food.

After 6 weeks the chick is no longer fed as it works towards its first flight that it takes about 4 or 5 days later. It’s large and heavier than its parents at this point, which helps it survive until it manages to provide for itself. For the young fulmar’s early years it spends its time out at sea and may travel far afield before visiting breeding colonies when it’s about 4 or 5 years old. The young bird is not likely to breed for another couple of years as it needs to find a nesting site and partner. Some young birds may jump the gun and breed with a mate whose partner hasn’t returned to the nesting site. It is normal for fulmars to be around 9 years old before they first breed and it can take some time before they become fully accustomed to parenthood as experience and success improves over the years.

Being a fulmar can be dangerous as there are plenty of predators looking for an easy meal. However these remarkable birds have a very effective weapon that is developed at a fairly early age. Using the oily wax from their proventriculus, they project this potentially lethal substance from their mouths for a few feet, giving the predator a nasty shock. When stuck in a bird’s feathers, the wax can prevent flight.

On a Personal Note:

We find fulmars incredibly enjoyable to watch and never get bored of seeing them. Visiting St Kilda, Scotland, was a very special experience and the area in which we camped was dominated by the ‘chattering’ of fulmars.

Looking over the highest sea cliffs in the UK, close views can be had of the fulmar’s nesting sites as they look curiously up at you. It’s definitely not for anyone afraid of heights though as the drop is enormous!

Whilst we marvel at the hard work that goes on by many species in the breeding season, they can’t always been 100% perfect all of the time. We watched as one fulmar landed in our camp looking rather confused. After wandering about for a while, it seemed to decide it was in the wrong place and did another flight circuit to try and get its bearings!

Fulmar Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

Learn more about the fulmar on the RSPB website.

The full name of the paper we refer to (written by Mallory and Forbes) is “Sex discrimination and measurement bias in Northern Fulmars Fulmarus glacialis from the Canadian Arctic”.

Additional Reading:

We have used a variety of sources for our research on fulmars, but one that has been particularly useful is Marianne Taylor’s “RSPB Seabirds”.

For more information on the relationship between the St Kildans and fulmars, you may enjoy this book:

Comments

We love to know your thoughts on our articles so greatly appreciate you taking the time to comment. We may be unable to reply directly but are in the process of creating a FAQs page to answer any questions. We currently check all comments before they’re posted so they do not appear immediately on the website.

Thank you for visiting www.embracenatureuk.com!

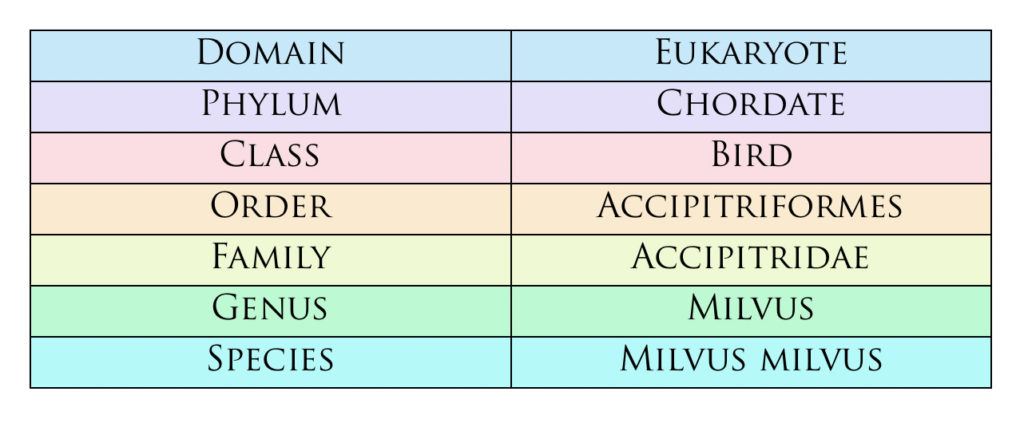

Scientific Name: Milvus milvus

Wingspan:

Approximately 145 – 195 cm

Description:

The most notable feature on a red kite is its forked tail. They tend to twist and turn their tail in flight in order to maintain control. Adults appear red in sunlight but juveniles exhibit less prominent colours and almost look washed-out in comparison.

A red kite’s call usually contains one long whistle followed by around 4 sets of shorter whistles that fall to a lower note during the call. The 4 sets are all uniform.

Red kites are quite common now in a lot of the UK as a result of successful reintroduction. For good close views visit feeding stations (see useful links below).

Identifying Sex:

The easiest way to tell males and females apart is when you see them together. They display the same colouration but the females are often larger than males. Males can normally be seen moving their tails more than females do and the tail is likely to be more deeply forked.

Their courtship display is enjoyable to watch as they twist and turn in the sky; sometimes flying towards each other to pass food or or pull away at the last second.

Diet:

Red kites are often opportunistic when hunting and are known to take small mammals and other creatures of similar size on occasion. They mostly eat carrion and supplement it with worms.

Breeding:

Red kites normally mate for life though sometimes an unsuccessful breeding season may prompt them to find a new mate. They’re generally ready to breed from within their second or third year. They take to the skies around March to perform their courtship ‘dance’ and at this time they will also begin to build their nests. Nesting takes place high up in the trees but the nests are built in an easily-accessed location for the birds.

In April the female lays between 1 and 4 eggs. Both the male and female incubate the eggs for around 30 or so days with the female doing the majority of the incubation. There is often some delay between the hatching of the eggs, which ensures that the eldest chick stands the best chance of survival if food is short.

The red kites fledge at around 7-8 weeks old though may still benefit from food provided by their parents for their first two weeks of freedom.

On a Personal Note:

We are very fortunate to be based in an excellent area for red kites and so have enjoyed the opportunity to regularly observe their behaviour; from their courtship dance to litter-picking from the street. This litter will then have been used to line a nest. The kites can be entertainingly acrobatic but more often than not can be observed soaring over a variety of habitats including motorway verges. Some of our most numerous sightings of birds of prey have been on the motorway though this bird-watching activity is best left to passengers!

From years of running around the countryside and sometimes running very poorly, it often feels that red kites are flying close by awaiting the moment where we drop dead from exhaustion. None of us have yet been eaten by a red kite, but there is still time…..

Red Kite Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

Read more about red kites on the RSPB website here.

Find out more about Yorkshire’s red kites here.

Read more on ‘The Wildlife Trusts’ website.

See what the ‘Chilterns’ website has to say about red kites.

Learn more about red kites from www.redkites.net.

Plan a visit to Gigrin Farm to get a closer look at these marvellous birds.

Or plan a trip to Llanddeusant to witness the kites.

Additional Reading:

Check out these books from amazon.co.uk:

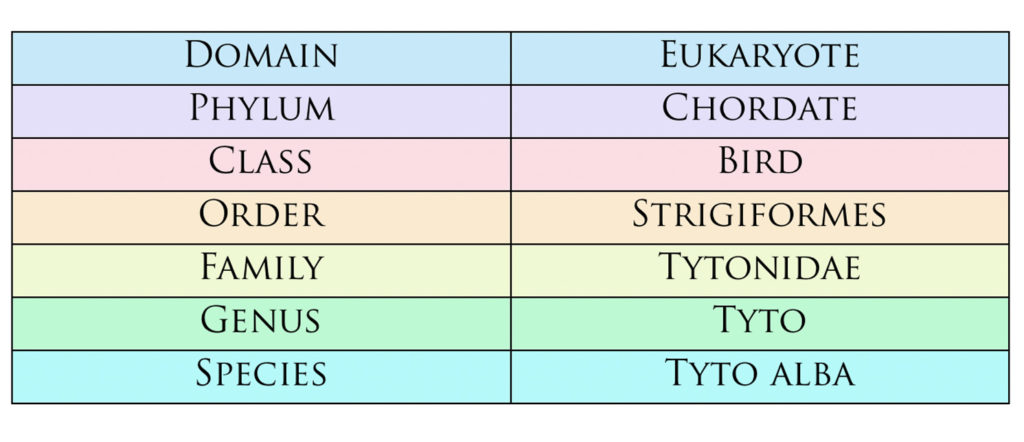

Scientific Name: Tyto alba

Size:

A barn owl is approximately 34 – 38 cm in size.

Description:

Barn owls are normally nocturnal or seen around dusk and dawn but it is not unusual to see them during the day if necessity calls. They are easy to identify when flying as often appear white against the landscape although they may be more difficult to spot when sat. Look out for them in areas of wild grass or meadows though they can also be found in other areas such as woodlands or appear alike to a ghost passing in front of your windshield when driving. Their hissing call is distinctive although you may find it daunting when heard at night.

Identifying Sex:

Male and female barn owls are similar, however, females can usually be determined by black spots under the wings and darker feathers. This is not foolproof as males sometimes exhibit the same features though most males are paler than females.

Diet:

Barn owls usually eat small mammals such as voles, shrews and mice. They cough up pellets, which contain the indigestible elements in their food. Their pellets tend to be almost spherical or cylindrical in shape and are relatively smooth. They are usually found in areas where the owl roosts or nests. Fresh pellets are dark in colour and get lighter with age. Barn owl pellets are generally around 2.5 – 3.5 cm in diameter.

Breeding:

Barn owls have the ability to breed from within their first year of age. The breeding season usually begins around March and is generally over by August though there are exceptions. Once a breeding site has been chosen, barn owls will spend time bonding and males will do more hunting whilst the approximately 350g female gains weight to reach her optimum breeding weight at around 425g. She will lay around 4 – 6 oval, white eggs on a nest of pellets. The laying of eggs is spread out over approximately 8 – 21 days so that meeting feeding demands of hungry owlets will be more manageable. Not all eggs are likely to hatch but after incubation of approximately 31 days, the eggs usually begin to hatch in order of laying.

On a Personal Note:

Over the years we’ve seen a lot of barn owls. Some have been over untamed grassland, others on farmland or in woodland. We’ve noticed they follow a similar routine on most evenings and therefore we have been able to see the same barn owl repeatedly.

Checking fence posts and trees are a good way to spot them if they’re there and it helps to carry binoculars though barn owls are quite easily identifiable without. The hissing call goes from being frightening in a lonely location on a dark night to something desirable and familiar once heard enough.

Whilst many people will describe barn owls as nocturnal, we have seen barn owls during the day plenty of times and watched a parent hunting all day every day whilst we were on holiday once in the South of England; disproving the traditional assumption completely. Barn owls are well-distributed around the UK and a variety of barn owl species exist around the world.

Barn Owl Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

One of the best sources for further information about barn owls is the ‘Barn Owl Trust’ website: www.barnowltrust.org.uk.

Read more about how the law protects barn owls on the RSPB website here.

Additional Reading:

Want to know more about barn owls?

Do you want to learn how to identify tracks and signs left by a range of animals and birds?