Scientific Name: Fulmarus glacialis

Size:

Length approximately 45cm, wingspan around 100 – 112cm

Description:

Fulmars are distinctive-looking birds with a bulky body, which is primarily white but for its grey back and wings. The wingtips are slightly darker than the rest of the wing. The bill makes the bird instantly recognisable as looks heavy with an obvious ‘tube’ on top. The fulmar is part of a group of birds often referred to as ‘tubenoses’ that have this feature. Many bird’s nostrils are contained within their bill but the ‘tubenoses’ are thought to use their unique feature to extract excess salt from their bodies that has been obtained when catching prey out at sea. It has been suggested that this adaptation also allows for a better sense of smell, which enables the birds to more easily find carrion. The bill is formed from a series of plates and has a hooked tip, that helps the bird keep hold of live prey.

The fulmar is the largest of tubenoses that breed in the UK. It has ‘stiff’ wings that are sometimes likened to blades cutting through the air. They seem to have no difficulty in flying and instead often glide with minimal effort. When juveniles lose their fluffy down they take on a very similar appearance to adults.

Whilst all of these features make the fulmar easy to recognise, a colour-morph exists that might confuse an observer. This alternatively plumaged bird is referred to as a ‘blue’ fulmar. The overall plumage is grey though the general appearance of the fulmar is still unmistakable. It is rare to see the ‘blue’ fulmar in the UK, however, you are more likely to see them in the North as the birds may visit from the Arctic.

Identifying Sex:

For the average bird-watcher, determining whether a fulmar is male or female is likely to be quite difficult. Their plumage is so similar that various studies ensued to try and find other ways of differentiating between sexes. A 2005 paper shows the research by Mark L. Mallory and Mark R. Forbes on fulmars in the Canadian Arctic. From measurements including head length, mass, bill depth and the size of the middle toe, they found that males usually are larger than females although some overlaps occur. Measurements of tail length proved not to provide a reliable comparison.

Diet:

Fulmars are pelagic (spend all but the breeding season at sea) and so their diet is mostly made up by fish, sand eels, zooplankton and carcasses from various creatures including whales and seals. They are thought to have a very good sense of smell, which leads them more easily to their food. This may also guide them to fishing boats, where they can enjoy a free meal. The waste from fishing boats is thought to have helped fulmar populations increase. The fulmars sometimes plunge dive for a shallow meal but they also pick food from the surface of the water; swallowing it straight away.

Breeding:

The UK enjoys large numbers of fulmars colonising the cliffs from around May until August each year during their breeding season. Once upon a time this wouldn’t have been seen in Britain as until 1878, the only part of the UK fulmars bred on was the St Kilda archipelago (Scotland). A community of people, who were reliant on birds such as the fulmar for survival, lived on St Kilda until August 1930. The changes in their lifestyle and population numbers has been thought to have affected fulmar populations and triggered their distribution to Shetland and beyond.

Fulmars return to the same partner and nest site each year with a few exceptions. They display to each other with bows, cackling and various other head and neck movements. Their partnerships are often long-lived with birds lasting into their 30s and in some cases to around 40 years old or more. A single egg is laid onto the cliff without the effort of a creating a purpose-built nest. For the first day the female incubates but passes the responsibility to the male for the next week whilst she’s away from the ‘nest’. They share incubation duties for the rest of the time in 3 or 4 day shifts. After 52 days the egg hatches prompting the parents to take turns finding food. For the first two weeks or so the chick has the company of one of its parents though after this time is often left alone whilst the adults forage for food.

After 6 weeks the chick is no longer fed as it works towards its first flight that it takes about 4 or 5 days later. It’s large and heavier than its parents at this point, which helps it survive until it manages to provide for itself. For the young fulmar’s early years it spends its time out at sea and may travel far afield before visiting breeding colonies when it’s about 4 or 5 years old. The young bird is not likely to breed for another couple of years as it needs to find a nesting site and partner. Some young birds may jump the gun and breed with a mate whose partner hasn’t returned to the nesting site. It is normal for fulmars to be around 9 years old before they first breed and it can take some time before they become fully accustomed to parenthood as experience and success improves over the years.

Being a fulmar can be dangerous as there are plenty of predators looking for an easy meal. However these remarkable birds have a very effective weapon that is developed at a fairly early age. Using the oily wax from their proventriculus, they project this potentially lethal substance from their mouths for a few feet, giving the predator a nasty shock. When stuck in a bird’s feathers, the wax can prevent flight.

On a Personal Note:

We find fulmars incredibly enjoyable to watch and never get bored of seeing them. Visiting St Kilda, Scotland, was a very special experience and the area in which we camped was dominated by the ‘chattering’ of fulmars.

Looking over the highest sea cliffs in the UK, close views can be had of the fulmar’s nesting sites as they look curiously up at you. It’s definitely not for anyone afraid of heights though as the drop is enormous!

Whilst we marvel at the hard work that goes on by many species in the breeding season, they can’t always been 100% perfect all of the time. We watched as one fulmar landed in our camp looking rather confused. After wandering about for a while, it seemed to decide it was in the wrong place and did another flight circuit to try and get its bearings!

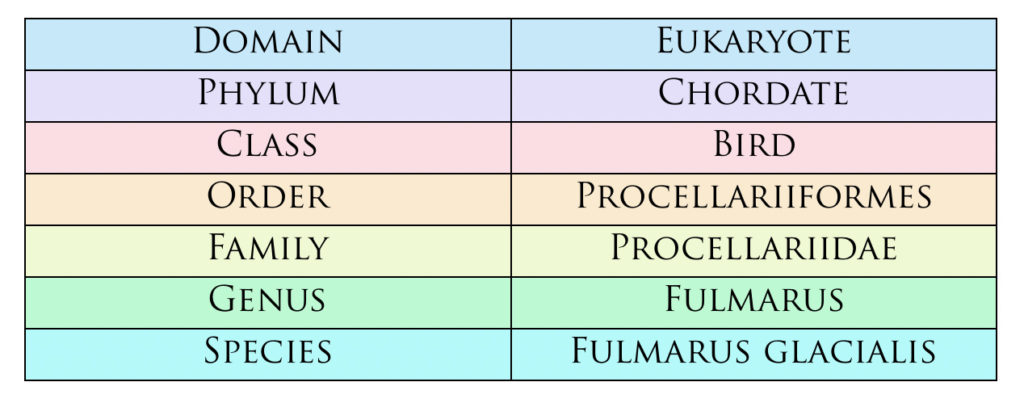

Fulmar Taxonomy:

Useful Links:

Learn more about the fulmar on the RSPB website.

The full name of the paper we refer to (written by Mallory and Forbes) is “Sex discrimination and measurement bias in Northern Fulmars Fulmarus glacialis from the Canadian Arctic”.

Additional Reading:

We have used a variety of sources for our research on fulmars, but one that has been particularly useful is Marianne Taylor’s “RSPB Seabirds”.

For more information on the relationship between the St Kildans and fulmars, you may enjoy this book:

Comments

We love to know your thoughts on our articles so greatly appreciate you taking the time to comment. We may be unable to reply directly but are in the process of creating a FAQs page to answer any questions. We currently check all comments before they’re posted so they do not appear immediately on the website.

Thank you for visiting www.embracenatureuk.com!